the steady, consistent progress of the Queen like a well-bred dreadnought. There is, however, one line which is just up, up, up, and that is the young Princess Diana’s; her evolution into global phenomenon is deftly charted here.

And the piece de resistance, the turning point, is episode six, Terra Nullius, where the Waleses take Australia during their Tour of 1983. Or rather, Diana takes Australia, in an unprecedented flash of star wattage.“It was celebrity on speed,” confirms the author Alexandra Joel, who was living in Sydney at the time of the Royal visit. This was Charles and Diana’s first official overseas tour together, the biggest trip by the Windsors Down Under since the Queen made her first ever foray there in 1954, and crowds came out in their tens of thousands: some 40,000 for one outing alone.

A young journalist – she would eventually become editor of Australian Harper’s Bazaar – Joel recalls “charging out of my office and jogging down the street and standing with the crowds and feeling terribly excited to catch a glimpse of this very pretty young girl in pink. I feel a bit mad saying it now”, she chuckles - she is, today, republican. “I have never in my life run out of the office and run down the main street to go look at somebody! But for that moment, she was the most famous woman in the world.”

She was, and not for that moment only. The Australia trip confirmed Diana’s emergence not just as a fairy tale princess, freshly married two years before, but as a global celebrity, a star of the type which would dwarf “ordinary” royalty — not least her husband. Charles, if ostensibly beside her, is really in her shadow - and boy does he know it.

This is something which Terra Nullius captures sharply, as well as offering some surprises, whether due to canny reportage or stylish embroidery. Did Diana really say ‘Ayers Dock’? Did she actually make faces behind her husband’s back as he made ponderous speeches? Was she so bereft at leaving Prince William, then nine months old, that she insisted on breaking engagements to go see him?

And more to the point, did she truly set back the cause of Australian republicanism by a generation? “Let’s face it, she’s made us both look like chumps,” says the Netflix version of the Aussie PM Bob Hawke, to Prince Charles, rueing that Diana’s popularity has stymied his efforts to get rid of the monarchy. This could kind of be true: after all, the Queen is still, in 2020, still queen of Australia. Although let us be clear: that line is not yet in any history books.

What is definitely true is that the tour itself was seismic for Diana. “She could not have been unchanged by the experience in Australia - nobody could have been,” says Joel. This was a world, of course, where celebrities were rarer, and existed in more rarefied circles, not blasted into our home every day via social media but pantingly covered by newspapers, magazines and TV channels.

Stardom was less easy to attain then, and Diana was a little naive about the effect she had on people. Crowds swamped her, to her shock, fear and pleasure - she reached out to them shyly, and they grabbed her right back. The problem is, not so much Charles. What he felt about this was something which, funnily enough, Joel’s parents also saw firsthand.

Sir Asher Joel was a high-ranking Australian official who had served with Prince Philip in the Navy during the War, so he and his wife Sybil inevitably attended balls and galas in the Waleses’s honour. Having just spoken to her widowed mother, now 96, about the Tour, Joel relays that Lady Joel could remember one thing quite clearly about Charles when she met him.

“I said, ‘How do you think he looked?’,” says Joel. “And she said: ‘Jealous’. And then she said, ‘Oh no, I probably shouldn’t say that: I’d rather say ‘put out’.” Joel then asked her mother why he looked like that. “And she said: ‘Well, I suppose he wasn’t used to sharing the limelight.’”

Some things to clarify. Yes, Diana was caught on film making an awkward little face when Charles talks about marrying her, something which does indeed lead him to ad lib tartly, “It’s amazing what ladies do when your back is turned”. Nor, sadly for Charles, is it a fabrication that he fell off his horse playing polo, flailing about as he tried to make a hit (some symbolism is too good to miss).

On the other hand, it hasn’t gone down in history that Diana said Ayers Dock, not Ayers Rock - not officially, anyway. Morgan has had unequalled access to archives and resources as he has pieced The Crown together, so he may well have squirrelled out something very obscure --- but suffice to say, ‘Ayers Dock’ is not the notorious gaffe it should have been, and Joel has no recollection of it either. “And everybody would have [remembered], because everybody would have said, oh, what an idiot. I mean, if it happened, it was certainly never publicised.”

Likewise, there is little trace suggesting that she gave up climbing Uluru (formerly, of course, Ayers Rock) only a few steps up. There is famous footage and photographs of her, quite striking in white against the deep Sienna red of the rock, but no reporting of her backing out due to feeling unwell (much to Charles’s displeasure). “Well, it is enormous,” laughs Joel sympathetically, but still it sounds unlikely to her. “Certainly, though, it was reported that when she first arrived at Alice Springs, she was very serious and she didn’t smile, and she seemed quite woebegone and overwhelmed.”

This is true from reports at the time: a report in The Age, dated March 21 1983, writes that Diana “seemed uneasy, even glum, and looked at the tarmac with downcast eyes”. It also jovially relays that the reason Diana may have been glum, as suggested by “a clucky English woman journalist” (oh dear), was because she was about to be separated from Prince William for a few days. This is made much of in The Crown - Diana’s refusal to even countenance leaving William behind in Britain, and then her determination to keep seeing him while on Tour.

On the plane over to Oz, she thoroughly berates a priggish courtier, Edward Adeane, for dismissing her and her child’s needs. The scene emphasises Diana’s strong maternal instinct and her dislike of court etiquette, both of which are well-known — but it is in many ways a fabrication. For one thing, Diana thought that Adeane, Charles’s private secretary, was “wonderful”, and was sad when he quit (exhausted by their arguments) a few years later.

For another, as she herself explains in Andrew Morton’s notorious biography, which she secretly provided most of the material for, she and Charles had accepted that that they would have to leave William behind in Britain, until an invitation from the previous Aussie PM Malcolm Fraser, Hawke’s predecessor, made them see it was a possibility.

“All ready to leave William,” she says in Diana: Her True Story. “I accepted that as part of duty, albeit it wasn’t going to be easy.” She and Charles never fought about it, and she certainly never rowed with the Queen, as was once reported. “We didn’t see very much of him [William], but at least we were under the same sky, so to speak.”

So, contrary to what the episode suggests, Diana doesn’t insist suddenly on bolting to see William after five days, and it’s not there, in the scenic Australian outback, that the couple had a dramatic showdown about their relationship - or a short-lived reconciliation. Yet as ever with Morgan, he has condensed the emotional truth of the matter. The Waleses’ marriage, two years in, was a mess.

Of course it was doomed from the start: it is a funny detail that Diana actually had been to Australia before, just days after the couple got engaged, to visit her mother, and the country was already offering a kind of omen: “It was a complete disaster,” she said later, “because I pined for him but he never rang me up.” In any case, her bulimia was well-known to The Firm by the time she got to Australia the second time, where its effects were unfortunately visible.

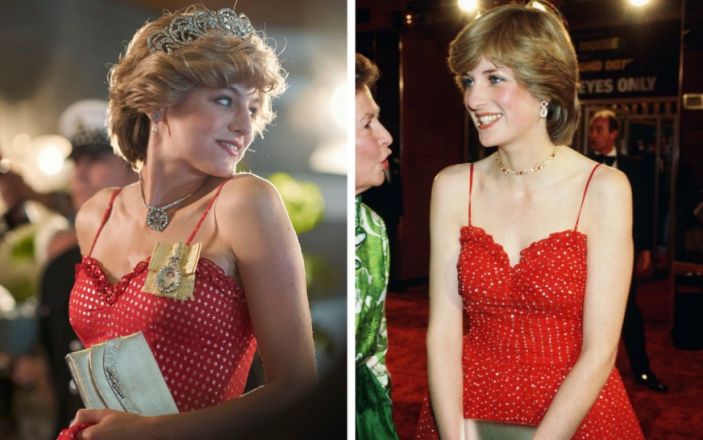

“I remember thinking, my gosh, she’s so thin!,” says Joel. “She wore lots of dresses with full sleeves and gathered skirts and things like that, so you couldn’t tell. But when you saw her in that blue ball dress” - where she famously danced with Charles at the Sheraton Wentworth in Sydney, a scene faithfully recreated by Netflix - “she was tiny. Absolutely tiny.”

Ultimately, Terra Nullius does also have a certain accuracy in that it reflects the ambiguousness of Diana’s triumph. Though it showed her how many people loved her, it was also an early taster of how mad and exhausting that adoration could be. She herself recalls the trip in mixed terms in the Morton book. “It was hot, I was jet-lagged, being sick,” she says, going over that dour appearance at Alice Springs. “I was too thin.”

She claims to have found the attention “just so appalling - I hadn’t done something specific like climb Everest.” And yet she also says she learned how to be a “Royal” in her first week there, and that “when we came back from our six-week tour I was a different person. I was more grown up, more mature…

And finally, though The Crown does show Diana to be startlingly fluent, very early, about her own emotional state, it is certainly correct in demonstrating that she had a natural instinct for connecting with others. “No one ever taught me how to talk to people,” she tells Morton, and though Diana was often an unreliable witness, this bit feels quite true.

As evidenced in her notorious Panorama interview, also in the news recently, Diana had a weird mix of natural charisma and artful whims -- one which not even she seemed quite in control of. “This was the thing [about her fame],” says Joel. “She both played to it and encouraged it, and yet also was repelled and trapped by it. You can see the genesis of that in Australia.”