“Such a sad day for Indian cinema”—it was this tweet by filmmaker Vishal Bhardwaj, quoting an article in Film Information, with which the Indian film industry woke up late on Tuesday night to yet another blow that it had been quietly dealt with by the government. That of the abolition of the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT).

FCAT used to hear appeals by filmmakers/producers aggrieved by the decision of the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC). With this statutory body now dissolved, the filmmakers are left with no option but to approach the High Court for the redressal of their grievances.

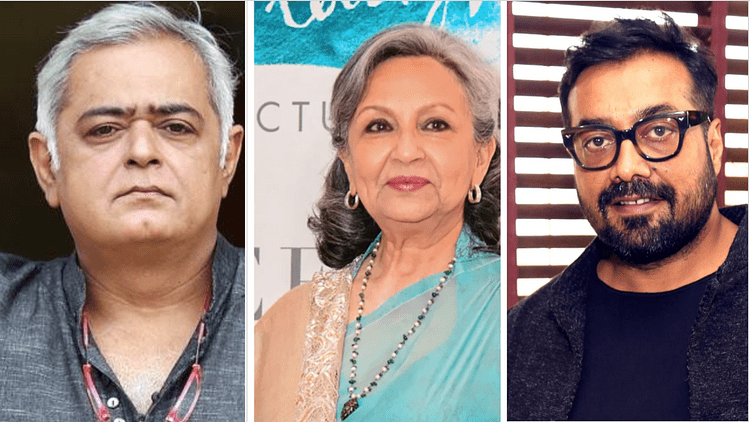

Most in the industry were taken by surprise by the news of the abolition. “We never saw it coming,” said filmmaker Hansal Mehta. But the fact is that it had been coming for a while as part of the government’s larger “streamlining” drive.

To this effect The Tribunals Reforms (Rationalisation and Conditions of Service) Bill, 2021 had been introduced in Lok Sabha by the Finance Minister, Ms. Nirmala Sitharaman, on February 13, 2021. The President promulgated the Tribunals Reforms (Rationalisation and Conditions of Service) Ordinance, 2021 with immediate effect on April 4, 2021, dissolving several appellate bodies and transferring their functions to judicial bodies.

Industry and legal experts are of the view that instead of regularising and systematising the film certification process (as envisaged by the ordinance), the abolition of FCAT would actually make way for more bottlenecks with the certification process getting messier, costlier and prolonged given that litigation in India is expensive and the courts are already stretched to their limits with the backlog of cases.

Moreover, the decision has been taken unilaterally without any discussions. “Why was it scrapped without any consultations with the stakeholders? It’s not in the interest of the producers,” says former CBFC chairperson, actor Sharmila Tagore.

“FCAT served a very good purpose. It was headed by a retired judge. If producers felt that CBFC was being unreasonable they could go to FCAT. It was like a bridge; less costly than going to court, heard both the parties and came to an amicable solution,” says Tagore.

“A whole new set of eyes, people of a certain stature would see your film [again]… It was the body to go to on hitting roadblocks with the CBFC. Most likely the decision would come through in your favour, you would go home and theatres would be your oysters,” says senior film critic and CBFC member Shubhra Gupta.

In fact, during her tenure, Sharmila Tagore had been of the opinion that FCAT’s powers should be extended and expanded so that it could also have the authority to address the innumerable irksome public interest litigations (PILs) that were getting filed against films like Jodhaa Akbar and The Da Vinci Code. That PIL tradition is still as painful and flourishing. The idea was to strengthen it to address all cinema related issues than have filmmakers rush to the nearest High Court.

However, filmmaker Prakash Jha says that he is not so disturbed by the development. Calling FCAT “infructuous”, he says that filmmakers had anyhow been rushing to the high courts with their films. For him access to the high courts and the Supreme Court is of prime importance. “There has to be a legal recourse open for the filmmakers,” he feels.

According to him, the abolition could be part of the larger drive by the government to make the processes less cumbersome and amalgamate various film bodies—like National Film Development Corporation, Directorate of Film festivals, Children’s Film Society of India etc—under one umbrella.

Delhi advocate Apar Gupta offers a different perspective. “The abolition of the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal is likely to increase further delay, costs and indeterminacy for film makers. The writ jurisdiction of the High Court will be an inadequate basis to remedy it… While in principle there are strong arguments for the abolition of tribunals, but — till film certification is mandatory —the FCAT was largely an imperfect but a functional body. Yes, it was even censorial but that provided relief in a large number of cases,” he tweeted.

One instance where it overruled CBFC decision in favour of the filmmaker was in 2017 in the much-in-the-news case of Alankrita Srivastava’s Lipstick Under My Burkha. The CBFC had refused to certify it but the film eventually got an “A” certificate with a few cuts after FCAT intervention.

“Even [ex CBFC head] Pahlaj Nihalani had to go to FCAT to get his Rangeela Raja (2018) cleared from the cuts that CBFC had prescribed. Imagine then how FCAT was a saviour of filmmakers when they had to rescue their films from Pahlaj Nihalani himself when he was CBFC chief,” says filmmaker Vasan Bala.

“FCAT was formed to provide fast track redressal to filmmakers who wanted to appeal against CBFC decisions. With its abolition, aggrieved filmmakers would have to now approach the HC, which means more often than not the appeals would keep pending for long periods given the workload of HCs. Also, it will take time away from HCs in dealing with important hearings,” says filmmaker Utpal Borpujari.

“You could go for redressal to FCAT without spending a lot of money, could argue and hope for a solution. How many producers can afford to move court?” asks filmmaker Hansal Mehta, adding that films like Udta Punjab could go to High Court against the ban because of the backing of big production houses like Reliance, Balaji Telefilms and Phantom.

Most would choose arbitration through a body like FCAT than a litigation. “90% producers would rather not go to courts and spend money and release dates will be an issue. When release dates are fixed and theatres booked then producers just don’t want to wait,” says filmmaker Anurag Kashyap. According to Ms Tagore, the move would cause untold problems to the producers who can’t afford delays on film releases.

For the film industry it means that one more layer of checks and balances and redressal is now gone. “It was a good thing to have. One more choice is always a choice,” stresses Gupta.

The abolition of FCAT would only add to the powers of CBFC with the filmmakers left to contend with its vagaries. It would mean either falling in line with the unreasonable aesthetic constraints imposed on them and altering and deleting scenes as per the demands of the censor board instead of spending months and years to settle things legally. “This will scare the producers and they would refuse to get involved with serious films,” says Kashyap.

Ironically, it’s not FCAT so much as CBFC that needs a total rethink and rehaul. However, the BJP government, which had promised to move away from censorship and implement the progressive classification norms suggested by the Shyam Benegal Committee, seems to have forgotten all about that rather easily and conveniently. Before that, there was also the Justice Mudgal Committee during the UPA regime that had prepared comprehensive and extensive guidelines for the implementation of the rating/classification system for films. The report got dumped in cold storage.

Instead of opening things up for the industry, the government is adding to the creation of a more restrictive environment. More constraints on filmmakers and sanitisation of content seems to be the stuff of the future of filmmaking in India. Keep watching this space.