I have been holding my sides watching two films back-to-back to dispel the Corona blues. There is an abiding moral in both.In Michael Moore’s Canadian Bacon, the US President builds up a war with Canada because his ratings in peace time are plummeting after the Soviet threat melted away in 1990-91. Peace destroys the business of his friend Hacker an arms manufacturer.

The other movie, Wag the Dog, has a spin doctor (played by Robert de Niro) and a filmmaker (played by Dustin Hoffman) collaborate to salvage the election campaign of a Bill Clinton look-alike, caught in a sex scandal two weeks before voting. The duet create a national hysteria about a war with Albania even though there is no war. It takes place entirely on TV channels.

The De Niro-Hoffman team has made the media eat out of their hands. The 72 days bombing of Serbia under Clinton’s watch and the carving out of Kosovo with its large Albanian population created a certain familiarity with Albania which otherwise would be totally unknown.

In Canadian Bacon an attempt is also made by the President’s men to persuade Russian President named Vladimir Kruschkin to start a mutually beneficial Cold war. A Cold war with Russia would help boost the arms industry. Kruschkin takes the sensible decision: he refuses to initiate a Cold war.

The media is central to Canadian Bacon. When the Commander of US forces, itching for action, gets ready to invade, the National Security Advisor intervenes. Military action with a weak country would end in a day. A huge quarrel with Canada has to be dragged on for a reasonable period, giving enough time for the American people to be mobilised. The President’s ratings would then skyrocket. The channels, with an eye on their own ratings, serve the national purpose by saturating the media space with war drums and startling revelations. Canada now has a nuclear bomb directed at America, an anchor announces, emoting with suitable anger.

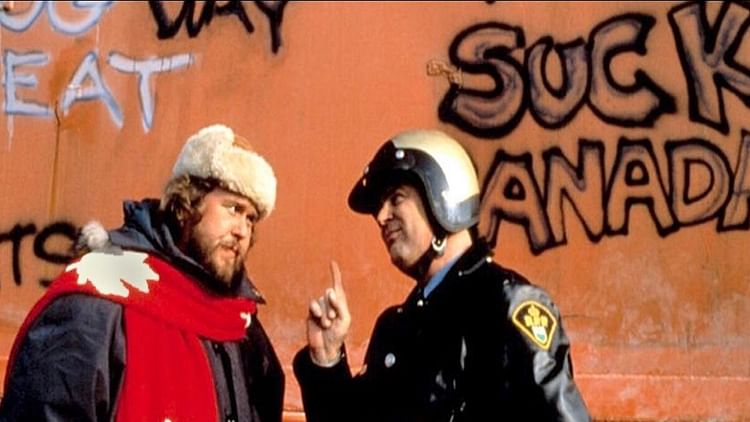

A charged-up Sheriff of Niagra county, Bud Boomer, distributes guns to an equally frenzied beer drinking clientele in the crowded bar, all riveted on TV which is focused relentlessly on the Canadian enemy.

Boomer’s girlfriend, Honey, who is also his well-armed deputy, will not wait for Washington to announce action. She has ideas of her own. To cut the story short, Honey climbs the pinnacle of the Toronto tower to hunt out secret codes designed to fire missiles aimed at America.

The last scenes of the film show her firing automatic weapons in all directions. She earns for herself high praise in the ending montage: she is named the ‘Humanitarian of the Year’ by the National Rifle Association. The delicious irony, in this vein permeates the body not only of Canadian Bacon but numerous satirical films.

Will Bollywood ever have the courage to mount such satire on the establishment? I suppose it is insensitive to ask such a question when a new Bill for double distilled censorship is being scripted.An overriding reason why such audacity cannot be on show here is because we are primarily a feudal people: irreverence is alien to our ethos. We have our parochial humour, but cannot laugh at authority. Iconography comes easy to us. We cannot satirise the ‘Mai Baap’. Some youthful stand-up comedians are trying but not without incurring the wrath of the cultural constabulary.

The baby must not be thrown out with the bathwater. Indian cinema has after all set high standards in portraying social reality. This was particularly true during the early days of Indian cinema. Penury inflicted on a peasant (Balraj Sahni) deprived of his patch of land for a factory, is the theme of Bimal Roy’s classic, Do Bigha Zameen. In fact, as early as the late 1940s, Chetan Anand’s Neecha Nagar has the landlord divert sewage water towards the township below to enhance the value of his land on high ground. The film was made 60 years before Roman Polanski’s Chinatown focused on the water wars in California, including in Los Angeles.

Japanese maestro Akira Kurosawa’s remark was on Satyajit Ray’s social realism. “Those who have not seen Ray, have not seen the sun.”Even though I have a sense of the reality, I was astonished nevertheless at the way Indian theatre or cinema ignored Enron, a scandal which had its centre of gravity in Maharashtra, home to Bollywood. There was an uproar with Shiv Sena and BJP taking the lead. The opposition to the deal was over high electricity tariffs beyond the reach of the poor. It collapsed. Enron, facing a host of other problems, declared bankruptcy. The CEO, Kenneth Lay, friend of George W. Bush, died a broken man.

Lucy Prebble wrote a superb play, Enron, which ran to packed houses at the Noel Coward theatre in London. Reception to the play at its Broadway premiere in 2010 was tepid. The corporate world smarting under the Lehman Brothers collapse did not accord the show much encouragement. Even though earlier David Hare’s Stuff Happens actually mimicked Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld and Condoleezza Rice for manufacturing the Iraq war.

Much of the script for Enron was centred on characters who negotiated the deal with Dabhol power project. Surely there is a vigorous enough amateur theatre in Mumbai to have picked up the script, isn’t it?

However, even in the West the audacity of screen and stage is singularly missing in mainstream media. This is particularly so since post 9/11 wars for which the media, by and large, became the drum beaters, compromising its own credibility. The adage, “When wars break out, the first casualty is the truth”, makes sense. This has resulted in the media’s declining credibility and, in consequence, a rise of “illiberal” democracies. When Donald Trump complained that “China is going ahead of us”, Jimmy Carter’s response was succinct. “China has not been to war since 1978; we have never stopped being at war.”