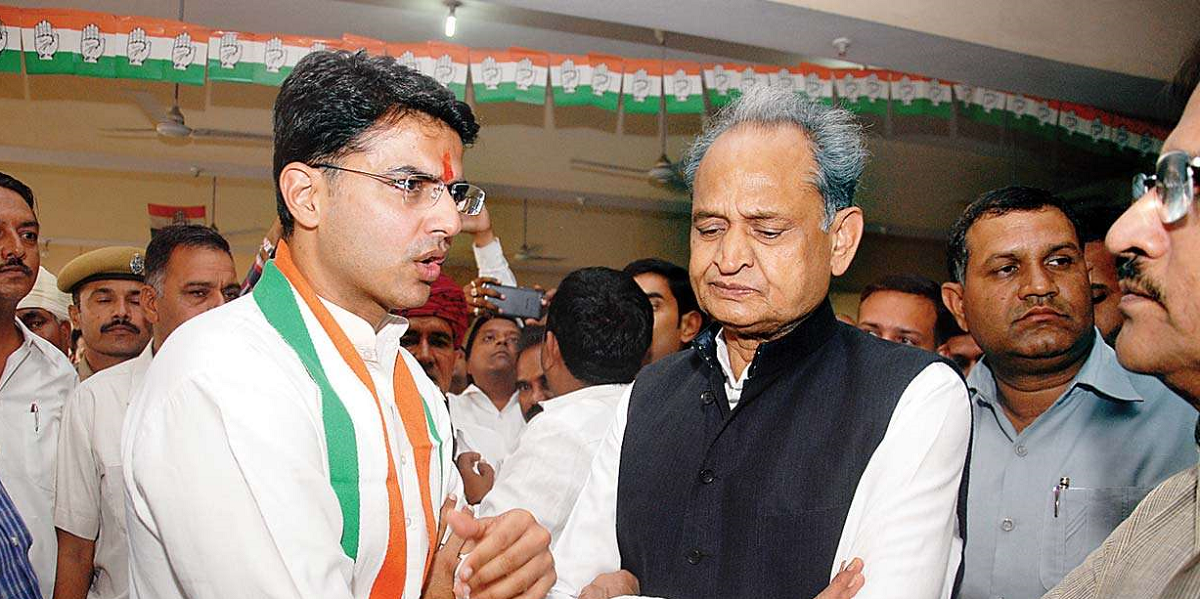

The political developments in Rajasthan have thrown up some interesting legal and constitutional issues.The legal battle started with the Congress party filing a petition before the speaker of the assembly seeking the disqualification of the rebel Congress MLAs led by Sachin Pilot. The term ‘whip’ used in the petition before the speaker has created a good deal of confusion in the legal circles. A whip is usually issued by a political party to its members in the legislature asking them to vote in a particular way in the house. In the face of a whip, if those members do not vote or abstain from voting, they are liable to be disqualified. But how can a party issue a whip to its members asking them to attend the party meeting and how can those members who do not attend that meeting be disqualified? This doubt naturally arose in the minds of laymen as well as lawyers. The arguments in the Rajasthan high court by the lawyer representing the rebel Congressmen indicate this was one of their key points.

The 10th schedule of the constitution (para 2 (1)(a) and (b)) specifies two grounds on which a member of the legislature can be disqualified. These are: (i) He has voluntarily given up his membership of the party, and (ii) He has voted or abstained from voting contrary to any direction issued by his party.

‘Whip’ – Much ado about nothing

In the Rajasthan case, the second ground is inapplicable because there was no occasion for a vote in the assembly. The Congress’s petition to the speaker, therefore, cites the first ground, namely, the rebel MLAs’ voluntary surrender of party membership. In this context, the confusion surrounding the term ‘whip’ needs to be removed. It is obvious that this term has been used rather loosely in the petition before the speaker.

However, it must be noted that the term ‘whip’ does not even figure in the 10th schedule, which uses the term “directions”. Of course, ‘whip’ is a commonly used and understood term in the legislatures which only means a direction issued by a political party to its members to vote or not to vote in the house. The term ‘whip’ used in the Congress petition before the speaker simply means a direction which was issued to the members to attend the legislature party meeting and it has nothing to do with voting in the house. The ground on which disqualification is sought makes this point absolutely clear.

This being so, it is very surprising that one of the top lawyers who appeared for the rebel Congressmen raised the ‘whip’ point and suggested that the Congress cannot issue one in the context of a party meeting and, therefore, the petition before the speaker should be quashed. Since the 10th schedule itself does not use the term “whip”, this argument has no merit.

Giving up membership of a party

The expression ‘voluntarily given up the membership of the party’ has not been defined in the schedule. But it has been interpreted by the Supreme Court in a number of cases in the past. These judgments make one thing clear – there is no universally recognised standard to ascertain whether a member has voluntarily given up his membership of the party. Each case has to be decided on its own facts are circumstances. However, a political party is not required to wait for rebels to do a series of acts before it can move the speaker seeking the disqualification on this ground. Just one action on the part of a member is enough to invite disqualification if it seriously affects the interest of the party.

In Rajendra Singh Rana Vs Swamy Prasad Maurya (2007), the Supreme Court says that one visit by the MLAs of the ruling party along with the members of the opposition to the governor seeking dismissal of their own government is sufficient to prove that they have voluntarily given up the membership of their party.

In this context, the court says, “no further evidence or enquiry is needed to find that their action comes within paragraph 2 (1)(a) of the 10th schedule”. This sums up the approach of the court to the issue of disqualification on the ground that a member has voluntarily given up the membership of his party.

In the Rajasthan case, things are fairly clear. The crucial meeting of the Congress legislature party was convened to ensure the support of its members to the government in the context of an alleged attempt to topple the government. So far as the ruling party is concerned, it was thus a very crucial meeting which had a bearing on the survival of the government. It was quite natural for that party to conclude that those who stayed away from the meeting had decided not to support the government, which could ultimately cause its fall. So, the ruling party moved the speaker to disqualify them on the ground that they have voluntarily given up the membership of their party. There is nothing unconstitutional about it.

When a speaker’s decision can be challenged

The rebel Congressmen deployed two heavyweight lawyers to defend their petition before the high court. It must be stated here that a petition at this stage is absolutely premature. The high court has the power to review the decision of a speaker. But the speaker needs to take a decision on merit first. Issuing a notice to the respondents by the speaker is not a decision on merit. Notice is issued as per the rules framed under the 10th schedule. Through the notices, the speaker asks the respondents to submit their replies to the petition so that he could go ahead and decide the question of disqualification. The courts have made it clear in a number of cases that it can step in only after the speaker has taken a decision on merit, not otherwise.

Even a review of the speaker’s decision on disqualification has a limited scope. The Supreme Court, in Dr Mahachandra Prasad Singh Vs Chairman, Bihar Legislative Council (2004), while explaining the scope of review, said as follows, “the decision of the chairman or the speaker of the house can be challenged on very limited grounds, namely, violation of constitutional mandate, mala fides, non-compliance with rules of natural justice and perversity”.

The courts have always approached the speakers’ decisions with caution and case. They have taken the view that if a speaker’s conclusion is reasonable, it will stand even if another equally reasonable view is possible.

Constitutionality of 10th schedule a settled matter

It is a bit surprising that the constitutionality of the 10th schedule has also been challenged in the petition before the Rajasthan high court.

This issue of constitutionality of the 10th schedule was settled long back by the landmark judgment of the Supreme Court in Kihoto Hollohan Vs Zachillu (1992). The five-judge bench summed up the point in the following words, “this is pre- eminently an area where judges should defer to the legislative perception of and reaction to the pervasive dangers of unprincipled defections to protect the community”. It is difficult to imagine how a high court can now reopen the question of the constitutionality of the 10th schedule.

A petition challenging the constitutionality of the notice issued by the speaker is a sheer waste of the court’s time. The speaker has acted in accordance with the rules. How can a notice become unconstitutional when it has been issued in accordance with the rules? The high court has got an opportunity to reaffirm the various decisions of the Supreme Court on this issue.