A charitable way of judging Narendra Modi’s government, which completed seven years in May, is that its propaganda has trumped over its performance. While this is of course true, it does not tell the whole story. A less charitable, and more telling, assessment would be that it has left the nation more divided on communal and political lines than at any time since 1947. The government has also rendered the institutions of democracy weaker like never before because of its systematic attempts to rob them of their independence and integrity.

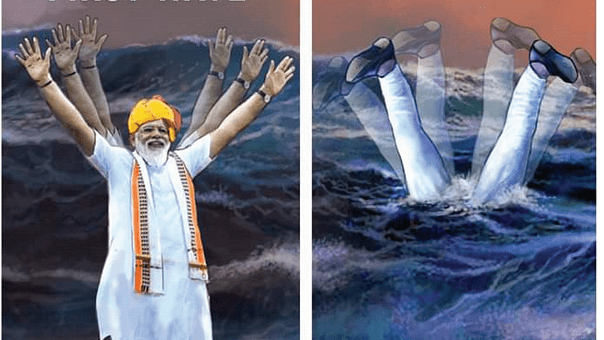

Modi came to power in May 2014 riding a huge wave of hope and expectation. What had contributed to his rise was a leadership vacuum in the Congress at the end of the second term of the UPA government, coupled with another leadership vacuum in the BJP created by a generational shift — both its stalwarts, Atal Bihari Vajpayee and L.K. Advani, were quite advanced in age. Modi used these two factors to his advantage to build a larger-than-life image totally disproportional to its substance.

He harnessed the power of media-hyping to project himself as a “strong leader” India needed and widely broadcast his “Gujarat model of development” that allegedly was far superior to anything India had achieved since independence. Also, with the help of Sangh Parivar’s foot soldiers, he emerged as the ‘Hindu Hriday Samrat’ — Emperor of Hindu Hearts. Finally, his promise of ‘Achche Din’ further served to swing the votes of the poor, the lower middle classes and the neutral segment of the electorate in his favour. The BJP for the first time received a clear majority in the Lok Sabha.

By the end of his first term in office, many of the hopes and expectations had remained unfulfilled. And even though it seemed that he would return to power — mainly because the opposition was still weak and divided — most political observers reckoned the BJP’s numbers would considerably come down in the 2019 parliamentary elections. But then Pulwama and Balakot happened, and the rest is history and still largely a mystery. Modi immediately changed the poll narrative to benefit from the anti-Pakistan mood sweeping across the country. The BJP’s tally shot beyond the 300 mark.

In a democracy like ours, there is a correlation between the size of the mandate and the size of the expectations of the people who deliver the mandate. When the voters give a leader a big victory the first time, and a bigger victory the second time, they also expect a lot more from him. So how does Modi’s performance stack up after seven years in office? Not in the opinion of the commentariat, but in the eyes of the common people?

The answer to this question is obvious. For the first time since 2014, Modi’s popularity is visibly waning. Not in one or some states, but all across India. How did this happen?

A PM lacking in not only ability, but also empathy

The most critical factor determining common people’s assessment of a leader’s and his government’s performance is how it affects their lives. Therefore, the state of the economy matters — specifically in terms of the prices of daal-chawal, jobs for the youth, incomes of farmers and entrepreneurs in the vast informal sector, cost of education and healthcare, and other usual pain points.

The economy was not a great success story even in Modi’s first term, and it is certainly not so far in the second term. However, the government’s glaring shortcomings in managing the economy were effectively covered up by its success in managing the media. Hence, the 2021 budget was praised by pro-BJP drumbeaters as a “once-in-a-century” budget.

But then something else unexpectedly happened. The Covid pandemic broke out in early 2020. The people initially put their full faith in Modi’s ability to tackle the crisis successfully. Responding to his call, they beat thalis and lit diyas in a novel show of national solidarity. They silently bore the agony of the prolonged nationwide lockdown, which he had announced by giving them only a four-hour notice. Even the plight of lakhs of migrating workers trekking on foot from cities to their native villages did not evoke strong criticism from the common people. The nation silently watched the government’s failure to make adequate preparations for their food and safe travel.

But the first phase of the corona crisis left the economy badly battered. Millions of people lost their jobs. According to research conducted by the Pew Research Centre, India’s middle class shrunk by 32 million and 75 million more Indians were pushed back into poverty. Those who had their ears to the ground could hear tales of families mortgaging or distress-selling their assets because their meagre savings had been exhausted. Modi no longer seemed either the saviour or the strong leader he was made out to be.

Another development around the same time made many of his own voters wonder if, in addition to lacking in ability, Modi also lacked empathy. Millions of kisans, first in Punjab and Haryana, and later in other states began protesting against the three farm laws, which the Modi government had enacted in a highly questionable manner — first in the form of ordinances and later without proper debate and voting in Parliament.

It soon became the world’s largest and longest peaceful agitation by farmers. Over 200 farmers died at protest sites. And all this was happening right next to the national capital. Yet, the prime minister never deemed it necessary to invite farmer leaders for direct talks with him. That he had expressed no remorse at the horrific communal violence in Delhi in February 2020, in which the security forces colluded with the rioters in targeting innocent Muslims was both understandable and predictable. But not being sensitive and responsive to the country’s farmers? For the first time, Modi, even to many of his supporters, looked arrogant and lacking in compassion.

A PM who declared victory over Covid prematurely… and caused immense misery to people

Now, what has decisively changed public opinion about the prime minister and his government is their gross mismanagement of the second wave of the Covid pandemic. In what has turned out to be the worst humanitarian crisis in independent India’s history, the entire Indian society is reeling under unprecedented pain and suffering.

Not just the sheer number of deaths but the avoidable ways in which many Indians died, and the utterly undignified ways in which they were cremated or their bodies were thrown into the Holy Ganga, has left the nation in a spell of shock. The international community, too, has viewed this tragedy with disbelief. Reports that the Indian government may be undercounting Covid-related deaths, and that the actual number could be much higher than the official data, are circulating globally.

In the face of this public health crisis, which has further exacerbated the economic crisis, the Modi government has exhibited its complacency, incompetence, and arrogance of power. Incidentally, the remark that the government was found to be “complacent” after the first wave of the pandemic was made by none other than Mohan Bhagwat, the chief of the RSS.

The government had ample time to plan and prepare for the second wave of the pandemic, which experts in India and around the world had forecast. It ought to have ensured life-saving oxygen supply and medicines, augmented beds and ICUs in hospitals, ramped up production and procurement of adequate vaccines for a speedy nationwide rollout, and improved Centre-State coordination for smooth implementation of all these tasks. In reality, it failed in each of these tasks.

If this has disenchanted the public, there are other reasons for Modi’s falling popularity. Both he and Home Minister Amit Shah set a bad example for the rest of the nation by violating their own government’s Covid-control guidelines and restrictions. They recklessly campaigned in the recent state assembly elections, most visibly in West Bengal. Incidentally, the government had influenced the Election Commission to hold an eight-phase polling spread over two months, just to enable Modi and Shah to campaign in the state extensively. Between them, the two leaders visited Bengal 38 times — Modi 17 and Shah 21!

That the BJP still failed to dislodge Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress from power — its tally failed even to touch three digits — tells its own story about Modi’s diminishing ability to win state elections.

The RSS chief ’s “complacency” jibe at the Modi government had another basis. As the second wave of the pandemic spread all over India, the nation, as well as the rest of the world, was aghast that prime minister himself took the lead in the government’s and the ruling party’s declaration of premature victory over Covid. In fact, they were in a self-congratulatory mood.

“We defeated Covid without vaccines” the PM told the chief ministers on April 8. Earlier, on February 21, the BJP had passed a boastful resolution stating: “It can be said with pride that India not only defeated Covid-19 under the able, sensitive, committed and visionary leadership of Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi but also infused in all its citizens the confidence to build an ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’. The party unequivocally hails its leadership for introducing India to the world as a proud and victorious nation in the fight against Covid19.”

Modi was present at the meeting of the party’s national office bearers, which passed this resolution. Obviously, he colluded in spreading the dangerous falsehood about India “defeating Covid”.

No amount of propaganda can hide common people’s disapproval of the prime minister’s performance because, this time around, they have experienced its negligence and ineptitude. They had earlier ignored the misery caused by his sudden announcement about demonetisation in 2016. They silently bore the effects of the steep rise in the prices of petrol and diesel, even though the price of imported petroleum products in global markets had significantly declined.

The protests against CAA and NRC, though intense, didn’t dent the prime minister’s image because the pliant media painted it as an expression of baseless Muslim angst. Millions of people suffered because of the sudden announcement of the lockdown last year, but this left no visible mark on Modi’s image. The kisan andolan created a lot of sympathy nationwide, but the government and the media still succeeded to a considerable extent in creating confusion in the minds of the urban middle class about the real issues behind the agitation.

However, for the first time now, Modi is staring at a situation where the people, including those who supported him earlier, are questioning him and his government — in their homes, in conversations among friends, in the social media and even in sections of the mainstream media.

Hence, non-BJP parties now have an opportunity, and a duty, to emerge as a credible alternative in 2024