What the media can never openly admit is that the largest peaceful democratic protest the world has seen in years – certainly the greatest organised at the height of the pandemic – has won a mighty victory.

Prime Minister Modi has announced he is backing off and repealing the farm laws in the upcoming winter session of Parliament starting on the 29th of this month. He says he is doing so after failing to persuade ‘a section of farmers despite best efforts’. Just a section, mind you, that he could not convince to accept that the three discredited farm laws were really good for them. Not a word on, or for, the over 600 farmers who have died in the course of this historic struggle. His failure, he makes it clear, is only in his skills of persuasion, in not getting that ‘section of farmers’ to see the light. No failure attaches to the laws themselves or to how his government rammed them through right in the middle of a pandemic.

Well, the Khalistanis, anti-nationals, bogus activists masquerading as farmers, have graduated to being ‘a section of farmers’ who declined to be persuaded by Mr. Modi’s chilling charms.

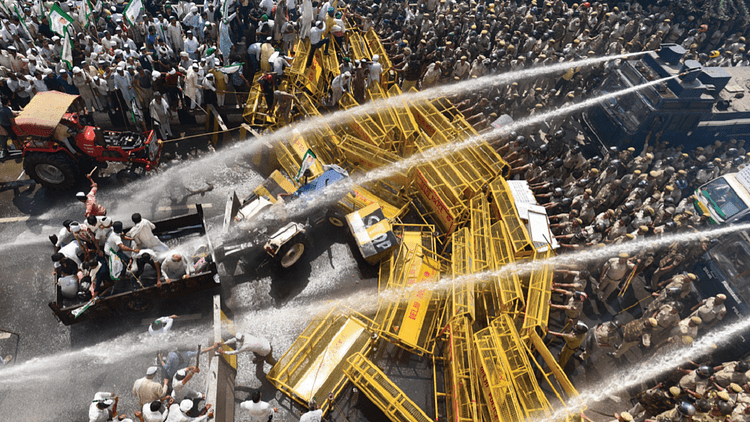

Refused to be persuaded? What was the manner and method of persuasion? By denying them entry to the capital city to explain their grievances? By blocking them with trenches and barbed wire? By hitting them with water cannons? By converting their camps into little gulags? By having crony media vilify the farmers every day? By running them over with vehicles – allegedly owned by a union minister or his son? That’s this government’s idea of persuasion? If those were its ‘best efforts’ we’d hate to see its worst ones.

The Prime Minister made at least seven visits overseas this year alone (like the latest one for CoP26). But never once found the time to just drive down a few kilometres from his residence to visit tens of thousands of farmers at Delhi’s gates, whose agony touched so many people everywhere in the country. Would that not have been a genuine effort at persuasion?

From the first month of the present protests, I was barraged with questions from media and others about how long could they possibly hold out? The farmers have answered that question. But they also know that this fantastic victory of theirs is a first step. That the repeal means getting the corporate foot off the cultivator’s neck for now – but a raft of other problems from MSP and procurement to much larger issues of economic policies, still demand resolution.

The anchors on television tell us – as if it is a stunning revelation – that this backing off by the government must have something to do with the upcoming Assembly elections in five states next February.

The same media failed to tell you anything about the significance of the bypoll results in 29 Assembly and three Parliamentary constituencies announced on November 3. Read the editorials around that time – and see what passed for analysis on television. They spoke of ruling parties usually winning bypolls, of some anger locally – and not just with the BJP and more such blah. Few editorials had a word to say about two factors influencing those poll results – the farmers’ protests and Covid-19 mismanagement.

Mr. Modi’s announcement shows that he at least, and at last, has wisely understood the importance of both those factors. He knows that some huge defeats have taken place in states where the farmers’ agitation is intense. States like Rajasthan and Himachal – but which a media, parroting to its audiences that it was all Punjab and Haryana, could not factor them into their analyses.

When did we last see the BJP or any Sangh Parivar formation come third and fourth in two constituencies in Rajasthan? Or take the pasting they got in Himachal where they lost all three Assembly and one Parliament seat?

In Haryana, as the protestors put it, “the entire government from CM to DM” was there campaigning for the BJP; even where the Congress put up a candidate against Abhay Chautala, who had resigned on the farmers’ issue; where union ministers pitched in with great strength – the BJP still lost.

All three states felt the impact of the farmers’ protests – and unlike the corpo-crawlers, the Prime Minister has understood that. With the impact of those protests in western Uttar Pradesh, to which was added the self-inflicted damage of the appalling murders at Lakhimpur Kheri, and with elections to come in that state in perhaps 90 days from now, he saw the light.

In three months’ time, the BJP government will have to answer the question – if the opposition has the sense to raise it – of whatever happened to the doubling of farmers’ incomes by 2022? The 77th round of the NSS (National Sample Survey, 2018-19) shows a fall in the share of income from crop cultivation for farmers – forget a doubling of farmer incomes overall. It also shows an absolute decline in real income from crop cultivation.

The farmers have actually done much more than achieve that resolute demand for the repeal of the laws.

Their struggle has profoundly impacted the politics of this country. As did their distress in the 2004 general elections.

This is not at all the end of the agrarian crisis. It is the beginning of a new phase of the battle on the larger issues of that crisis. Farmer protests have been on for a long time now. And particularly strongly since 2018, when the Adivasi farmers of Maharashtra electrified the nation with their astonishing 182-km march on foot from Nashik to Mumbai. Then too, it began with their being dismissed as ‘urban naxals’, as not real farmers and the rest of the blah. Their march routed their vilifiers.

There are many victories recorded by farmers. Not the least of which is the one the farmers have scored over corporate media. On the farm issue (as on so many others), that media functioned as extra power AAA batteries (Amplifying Ambani Adani +).

Between December and next April, we will mark 200 years of the launch of two great journals (both by Raja Rammohan Roy) that could be said to have been the beginning of a truly Indian (owned and felt) press. One of which – Mirat-ul-Akhbar – brilliantly exposed the Angrezi administration over the killing of Pratap Narayan Das from a whipping ordered by a judge in Comilla (now in Chittagong, Bangladesh). Roy’s powerful editorial resulted in the judge being hauled up and tried by the highest court of the time.

The Governor General reacted to this by terrorising the press. Promulgating a draconian new Press Ordinance, he sought to bring them to heel. Refusing to submit to this, Roy announced he was shutting down Mirat-ul-Akhbar rather than submit to what he called degrading and humiliating laws and circumstances. (And went on to take his battle to and through other journals!)

That was journalism of courage. Not the journalism of crony courage and capitulation we’ve seen on the farm issue. Pursued with a veneer of ‘concern’ for the farmers in unsigned editorials while slamming them on the op-ed pages as wealthy farmers ‘seeking socialism for the rich’.

The Indian Express, The Times of India, almost the whole spectrum of newspapers – would say, essentially, that these were rural yokels who only needed to be spoken to sweetly. The edits invariably ended on the appeal: but do not withdraw these laws, they’re really good. Ditto for much of the rest of the media.

Did any of these publications once tell their readers – on the standoff between farmers and corporates – that Mukesh Ambani’s personal wealth of 84.5 billion dollars (Forbes 2021) was closing in very fast on the GSDP of the state of Punjab (about 85.5 billion)? Did they once tell you that the wealth of Ambani and Adani (who clocked $50.5 billion) together was greater than the GSDP of either Punjab or Haryana?

Well, there are extenuating circumstances. Ambani is the biggest owner of media in India. And in those media that he does not own, probably the greatest advertiser. The wealth of these two corporate barons can be and is often written about – generally in a celebratory tone. This is the journalism of corpo-crawl.

Already there is bleating about how this cunning strategy – the backing off – will have significant impact in the Punjab Assembly polls. That Amarinder Singh has projected this as a victory he engineered by resigning from the Congress and negotiating with Modi. That this will alter the poll picture there.

But the hundreds of thousands of people in that state who have participated in that struggle know whose victory it is. The hearts of the people of Punjab are with those in the protest camps who have endured one of Delhi’s worst winters in decades, a scorching summer, rains thereafter, and miserable treatment from Mr. Modi and his captive media.

And perhaps the most important thing the protestors have achieved is this: to inspire resistance in other spheres as well, to a government that simply throws its detractors into prison or otherwise hounds and harasses them. That freely arrests citizens, including journalists, under the UAPA, and cracks down on independent media for ‘economic offences’. This isn’t just a win for the farmers. It’s a win for the battle for civil liberties and human rights. A win for Indian democracy.