Google Search for Web:

Kajal Agrawal

The state of the Republic: Staring at a dystopian future bereft of reason Featured

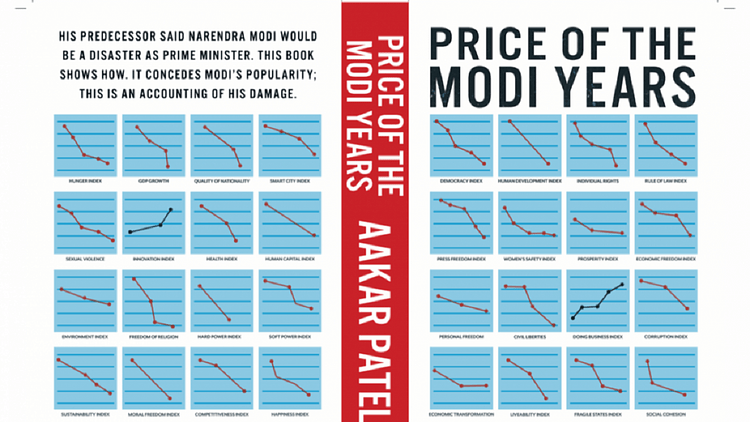

These extracts from the book ‘Price of the Modi years’ by Aakar Patel sum up the state of the Republic and reveal a reckless executive, an irresponsible media and a subservient and pliable bureaucracy

Manmohan Singh said, just before demitting office, that Modi would notmake a good PM. His exact words were: “I do believe that having Mr. Modi, whatever his merit, as the prime minister will be a disaster for India.” Singh is famously reticent and understated and so such a firm and direct opinion on Modi and the future was unusual and surprising.

A disaster for India in what way? This Singh did not say. Perhaps he thought he didn’t need to because it would become apparent.On a triumphal night in May 2019 (after winning a bigger mandate), Narendra Modi said: ‘Brothers and sisters, in our country no election has happened like this. You have seen that for 30 years especially, although the drama was going on for years, it had become fashionable to wear a tag called secularism. And there used to be chants for the secular to unite. You would have seen from 2014–19, that entire section has stopped talking. In this election, not even one political party has the guts to wear the mask of secularism to fool the country. They have been unmasked.’

This is quite true. Modi has taken India to a place where political parties dare not speak of secularism and pluralism though it is the basic structure of our Constitution.Years before Modi became chief minister, Ashis Nandy, along with the writer Achyut Yagnik, met and interviewed him. Nandy wrote:

‘It was a long, rambling interview, but it left me in no doubt that here was a classic, clinical case of a fascist…Modi, it gives me no pleasure to tell the readers, met virtually all the criteria that psychiatrists, psycho-analysts and psychologists had set up after years of empirical work on the authoritarian personality.'

'I still remember the cool, measured tone in which he elaborated a theory of cosmic conspiracy against India that painted every Muslim as a suspected traitor and a potential terrorist. I came out of the interview shaken and told Yagnik that, for the first time, I had met a textbook case of a fascist.’

On the morning of 25 October 2018, four men from the Intelligence Bureau were caught spying on the CBI director, whom the Modi government was trying to get rid of. The CBI was going through a period of turmoil caused by government meddling in the agency. Later the same day, the offices of Amnesty International India (where I was working) in Bengaluru were raided. The primetime debates that night were about the raid and not the fact that the Union government had been caught spying on the CBI chief.

The next morning, I got a call from an anchor who said that the previous night, the PMO had sent channels talking points on the Amnesty India raid and asked them to focus on it rather than the CBI.During the ‘raid’, I was questioned and my statement was recorded. When I asked for a copy of it after I’d signed it, I was told that it was confidential and would be given to me only if and when the case was formally prosecuted.

A few days later, my statement was read out during a two-hour debate on Times Now. When I asked ED officers why they were playing these games, they were apologetic and said Arun Jaitley’s office had given it to Times Now.On 19 June 2020, NDTV correspondent Arvind Gunasekar tweeted the text of a note the government had given to journalists as ‘talking points’ after an all-party meeting on the Chinese intrusion. This was the meeting in which Modi claimed that there had been no intrusion by China.

Gunasekar said: ‘This was circulated to media from PMO as “Govt Sources” even when the meeting was underway. Whoever drafted this, didn’t know that Naveen Patnaik didn’t attend the all-party meeting while Pinaki Misra represented BJD.’

The talking points that the Modi government wanted the media to focus on in their headlines included:

• India stands solidly behind PM. Most leaders express their confidence in way Modi Government has handled the situation.• Congress efforts to create wedges trashed by KCR, Naveen, Sikkim Kranti Morcha.The channels obeyed the instructions. The primetime debate for Times Now a few hours later was headlined: ‘All parties unite behind India but Sonia Gandhi won’t slam China?’.

In March 2020, the evangelical Muslim organisation Tablighi Jamaat held a meeting in Delhi from the 10th to 13th. This was scheduled before the onset of Covid-19 and they were congregating at a time when the Modi government was itself dismissive of the threat of the pandemic.

But as the cases in India began to rise towards the end of March, the government determined that it would scapegoat the Muslims and enlisted the media to do this, spreading the conspiracy of ‘Corona Jihad’. The Union made much of evacuating the area where the congregation was being held (Modi sent NSA Ajit Doval to ‘reason’ with the organisers, who had been asking for safe evacuation for days).

Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal called the gathering at the centre ‘an irresponsible act’. ‘The main reason for increased number of cases is that members of the Tablighi Jamaat have travelled across the country,’ said Lav Agarwal, Joint Secretary of the health ministry at a press conference. Also on 1 April, the BJP’s IT cell head Amit Malviya tweeted that the Tablighi gathering was akin to an ‘Islamic insurrection’. Kapil Mishra accused the group of ‘terrorism’.

On 4 April, Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS) chief Raj Thackeray suggested that the group’s members be shot: ‘The meeting of Tablighis had taken place at Markaz in Delhi. Such people be killed by firing bullets at them. Why give them treatment?” In Uttar Pradesh, the group’s members were jailed and booked under the anti-terror National Security Act.

During the months of active persecution, the group’s members, including foreigners, were jailed and charged with attempted murder. The theories being promoted were that they were deliberately spreading the virus around India by getting themselves infected, spitting on fruit, refusing to wear masks, running around naked in their wards, harassing nurses and so on. None of this was true.

Without being convicted and even without any evidence, Jamaat members were ‘blacklisted’ from receiving visas in the future. In June, the Modi government amended the policy for visa applications to India to introduce a Tabligh-specific clause. This was the first time in India that a particular religious group had been mentioned in the list of visa guidelines.

A Muslim security guard had an FIR filed against him for ‘giving’ his employer Covid. The police said the guard’s mobile phone records ‘had placed him in the Nizamuddin area’, near the Tablighi Jamaat gathering.

The guard turned out to be Covid negative.

On 6 July, before the chief metropolitan magistrate at Delhi’s Saket court, 44 Tablighi Jamaat members refused to pay a fine of between Rs 4,000 to Rs 10,000 in exchange for closing of cases and bravely chose trial. By December, eight months after 11 states had filed 20 FIRs against more than 2,500 Tablighi Jamaat members, nobody was convicted.

Judges called the cases ‘malicious’, ‘a virtual persecution’, ‘abuse of process’, ‘abuse of power’, and said the Tablighi Jamaat members were ‘scapegoats of a political government’ who had acted against the group though having ‘not an iota of evidence’. Yet an enormous amount of State resource and time had been expended in pursuing the conspiracy theory.

The abolition of the Planning Commission by Modi had severed the political link that was present between the Union and the states. The Planning Commission was concerned with the development of states. Its replacement, the NITI Aayog operates as Modi’s personal think-tank; there is no accountability and therefore it is free to do whatever takes its or, more precisely, Modi’s fancy.

It has sprung to the defence of Modi’s most eccentric initiatives and provided some convoluted justifications for them. It has busied itself with producing clickbait lists— aspirational districts, innovation index—and engaged in other meaningless and ultimately pointless exercises. Every so often it makes asinine statements.

NITI has no real relationship with the states, unlike the Planning Commission, with which they had, whether positively or negatively, as with chief minister Modi, robust engagement.

In 2015, the government accepted the recommendations made by the 14th Finance Commission set up by Manmohan Singh that states would get a 42 per cent share of Unioncollected taxes, up from 32 per cent. This was celebrated as a great act of federalism.

Modi wrote a letter to chief ministers: ‘This naturally leaves far less money with the Central government. However, we have taken the recommendations of the 14th Finance Commission in a positive spirit, as they strengthen your hand in designing and implementing schemes according to your priorities and needs.’

What followed is instructive. In the first year of the award, the actual share the states received fell from the promised 42 per cent to 34 per cent. By 2020, it fell further to 30 per cent, below even the original 32 per cent, leave aside the aspired for 42 per cent.

Why was this? Because the Union was consistently increasing its share of taxes through endless cesses and surcharges, from which states received no share because they were raised for specific central causes: Swachh Bharat cess, Infrastructure cess, Health and Education cess, Agri Infra cess and so on.

Money taken by the Union as cess, cutting out the states, quadrupled between 2014 and 2020. The proportion of cess and surcharge collected as the Union’s gross tax revenue doubled under Modi, leading to complaints from Opposition-led states. Having tossed aside what had been recommended and seemingly accepted previously, the 15th Finance Commission was given a mandate that was openly contemptuous of the states.

And it was clear that there was to be a reneging on Modi’s previous acceptance of giving states a fairer share: the commission was asked to assess ‘the impact on the fiscal situation of the Union Government of substantially enhanced tax devolution to States following recommendations of the 14th Finance Commission’.

Modi’s 2019 manifesto said he would ‘work towards improving GDP share from manufacturing sector’. To that end, Modi launched the ‘Make in India’ scheme in September 2014; it was one of his first big launches, with a striking logo of a lion striding forward. An American firm was asked to make the logo, for which it charged Rs 11 crore.

The Make in India website says it ‘aims to raise the contribution of the manufacturing sector to 25% of the GDP by the year 2025 from its current 16%’. This was a classic Modi scheme: mostly logo and name and little actual strategy, detail or follow-up.

The results were visible soon. In 2019, according to the World Bank’s data, instead of growing, the share of manufacturing in GDP fell to 13.6% percent from 16 percent. It fell further in 2020.In the same period, Bangladesh’s share of manufacturing rose from 16 per cent to 19 per cent, and Vietnam’s rose from 13 per cent to 16 per cent. So, increase was possible, but it required thinking and application rather than mere announcement and spectacle, which made it difficult to be achieved under Modi.

Six years after Make in India was launched, data showed that industry’s share of GDP in India was at a two-decade low, falling behind Sri Lanka. Modi had managed to reduce manufacturing’s share by 2.5 per cent over what it had been under Manmohan Singh.

Latest from Super User

- Sushmita Sen to Harnaaz Sandhu: Indian Miss Universe pageant winners who stole our hearts with their winning answers

- Thousands of Migrants Form Caravan to Reach U.S. Before Trump Takes Office

- How players are selected: The IPL Auction 2025 order

- ICC Issues Arrest Warrant For Benjamin Netanyahu

- Russia deploys 24 ships with Kalibr missile carriers to Black Sea